Issue 1.3 | Tenderness

It’s no surprise that this issue comes during the dead of winter as a cozy reminder that we are not alone in our experiences with the hostility of the elements. If anything, together we are able to look back at these moments through the warmth of our memory. This issue represents exactly that.

This issue explores our search for joy in our contemplation of the mundanity of life and its challenges. Whether seeking shelter from the bitter cold or comfort in the unknown, flo. online Issue 1.3 asks you to reflect on your own life, even the most bittersweet moments, with tenderness.

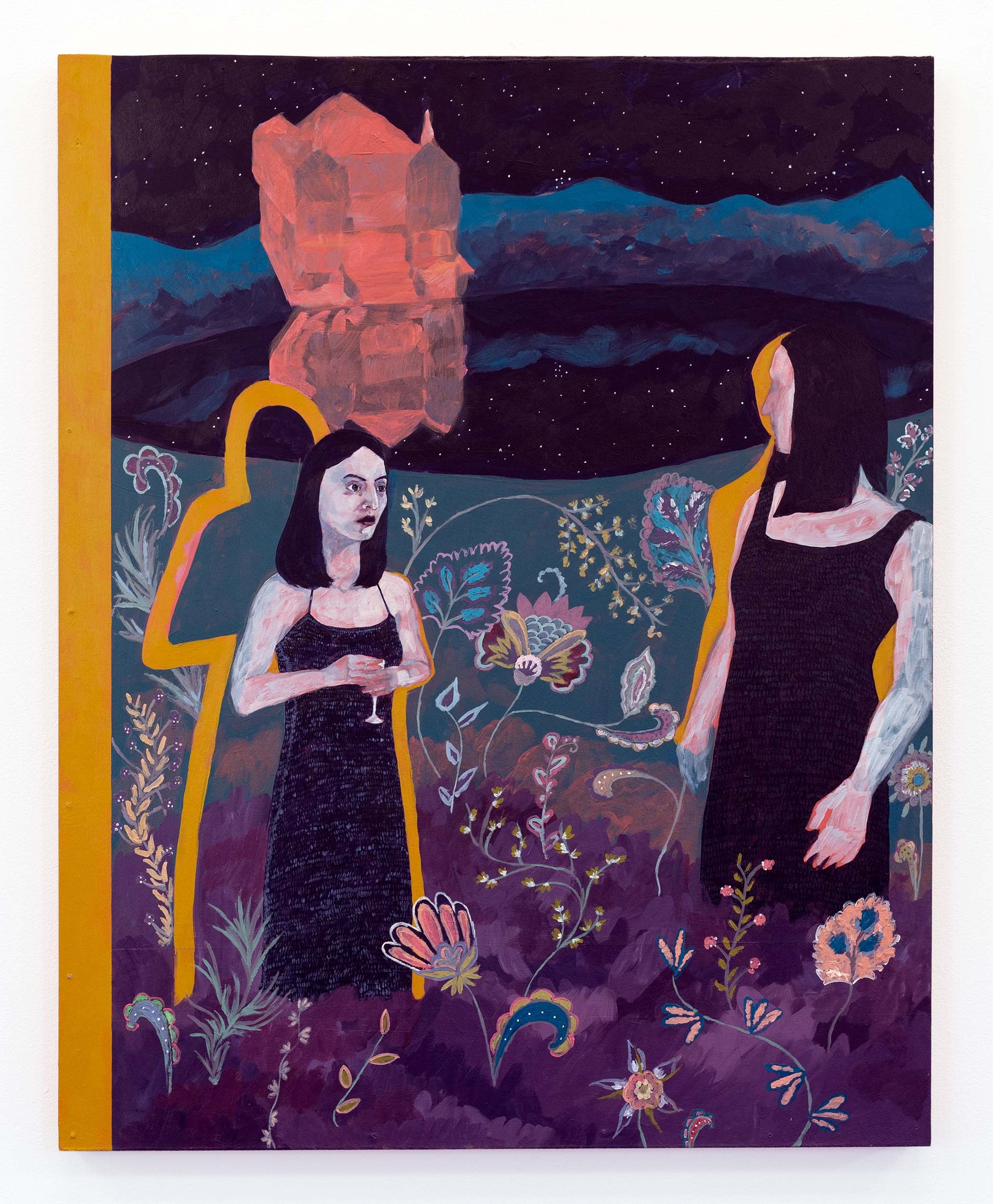

In the dream the sky is pink and my hands are red

Senka Stankovic

Senka Stankovic (she/her) is a painter and writer based in Ottawa, Ontario. Senka holds a BFA in visual arts from the University of Ottawa, and is working towards a Master's in Information Studies. She is a co-founder and editor-in-chief of flo. literary magazine.

Frozen Morning

Carter Vance

Cut in drift of falling snow,

left shaking shadow in wake,

lying in open window chill,

for plans made of tomorrow

already drifted past.

Curfew and persuasion were

companions at will, summoned to

keep calm when days went slowly

and nights were unloved for all

they lacked in excitement.

Starting a howl up to distant

listeners, reaching past air of

short towers and splintered alley,

cracks in windshield on parking

space for warmth here.

Cursing transparent of old ambition to

new potted plants, sick in bed,

watching wallpaper turn shades

each half-light with age, over

with what was.

Carter Vance is a writer and poet originally from Cobourg, Ontario, currently residing in Gatineau, Quebec, Canada. His work has appeared in such publications as The Smart Set, Contemporary Verse 2 and A Midwestern Review, amongst others. He was previously a Harrison Middleton University Ideas Fellow. His latest collection of poems, Places to Be, is currently available from Moonstone Arts Press.

The Riser

Andrew Lafleche

I.

I used to think her lazy in rise

the lackluster climb from below

intrusive glare through the window

a magnifying glass threatening the ant:

Leave the overlooked unexposed.

Those depths in a man which never

experience light, less prelacy revealed

under a surgeon’s knife, holding to account

the body, for all he fails to remember

and chooses not to be made right.

II.

He said she said by the seashore

castles erected over eroding footprints

stand out from the storm, where:

The rain fell, and the floods came,

and the winds blew and slammed,

presages of the greatest of totters

whilst skulking another’s plan—

As the Osprey hovers above the

line of tidal retreat, mesmerising

his prey into belly-up defeat.

III.

A crop of trees sprouts in the valley

the space between meadow and here

sun advancing the waning moon

above the light fantastic diamond dew:

The sleeping verdure asleep no more.

Fife, five. Fow-er, four.

Three, tree. Too, two and wun.

One.

All life in wait of release.

All of life waiting to be received.

Andrew Lafleche is an award-winning poet and novelist from St. Catharines, Ontario. He served in the Canadian Armed Forces, and later received an M.A. in Creative and Critical Writing from the University of Gloucestershire. He now lives in the Ottawa Valley and serves as a volunteer firefighter in his community. Visit AndrewLafleche.com or follow @AndrewLafleche on X for more information.

On The Surface of The Pond

Anna Idelevich

A calm night, a ray of light pours in and emboldens,

the wind calls the swans in the pond, the water flows,

in the illumination there are stalks of reeds and cattails,

wine-tinged ribbon of dripping starry tears,

a sore thing that has undergone sweet bliss, a prognosis.

Tell me, where does the frost really come from?

And the crunchy thing that sang to me, you are a virtuoso in singing.

I won’t stop loving you, I couldn’t forget you,

sore, sore, the pond is the lake of dreams.

Anna Idelevich is a scientist by profession, Ph.D., MBA, trained in the neuroscience field at Harvard University. She writes poetry for pleasure. Her books and poetry collections include “DNA of the Reversed River” and “Cryptopathos” published by the Liberty Publishing House, NY. Anna’s poems were featured in Louisville Review, BlazeVOX, The Racket, New Contrast, Zoetic press, Shoreline of Infinity among others.

A Bus Stop Away

Danie Maxelus

It was my first winter here, and everything felt so cold. The first thing I noticed about Canada was the bright red bus stops. There was always garbage everywhere, and the big red doors closed slowly, letting the cool breeze disturb the warm temperature that the heater splattered on us. If it weren't for the murmur of a few people and the loud bus stopping outside, with the hurried steps of passengers getting off, the station would be silent. Only the crunch of boots on the snow sang to us, only the chattering teeth talked to us.

The first time I saw snow was back in Haiti on my TV. I always thought it looked very amusing. I used to believe snow would be warm and fluffy like cotton candy, and malleable to the touch, almost like making ice cream balls. Instead, it was brown and yellow, covered in footprints, and also runny and slippery like a slip and slide.

In the airport, my mom gave me an overprotective coat to shield me from the snow. After the long ride in an uncomfortable chair and unseasoned food, she warned me of Canada's mischievous weather. The coat was stuffy, and the oversized multicolored scarf around my neck kept rubbing my nose, which was really tingling. My sleeve kept falling, and my mittens made my hands so uncomfortable. My boots were cozy, but putting them on at the airport was a struggle, only because my mom demanded I wear oversized socks with them as well.

"I know you will thank me once your toes start freezing," she lectured.

The bus stops in Haiti were just the side of the road; it was familiar. The road the bus would take was the same one I took to go to school for 6 years. The drivers were never late because there was never a time scheduled for them. Usually, you gave him $5 and got off when needed, knocking a small pencil on the back of their truck that was lightly held with rubber bands. Here in Canada, the bus stop was big, with a screen showing the time it was supposed to arrive (all of them were late).

My hands that once burned from the cold now tingled from the uncomfortable heat stored, and I felt like my hands were paralyzed in a ball. "Here, the bus driver leaves fast. They don't care because Ottawa buses are always late during winter. We must wait for the bus and not be late or else you’ll get sick" My mom added while readjusting my scarf.

I wanted to go outside to cool off, but my toes started freezing, and my fingers burned as if I had put them on fire. Somehow the snow had entered my shoes, and the large socks did not protect me from this unusual habitat. Once the bus came (20 minutes late, of course), we entered carrying our heavy bags. My mom, with a big smile saying, 'God bless you,' tapped a card into a green box, while I hated the bus driver for making us wait. So, I didn’t smile back at him.

Everything looked the same in Ottawa, while in Haiti, the mountains had curves, and the trees differed from place to place; the neighborhoods had different smells, roads, and even people; it was easy to find your way if you got lost. But in Canada, everything looked white. A bus ride to unusual places was exhausting. My socks felt like mud, cold and wet, which made the big boot feel hollow, my hands continued to burn from the hot-cold affair, each finger screaming for release and tip red from abuse of the weather, my hat uncomfortable on top of my head itching my ears like tiny needles on my braid, and standing in the snow for 20 minutes was tiring. I wanted hot milk with bread and to see my country's warm summer sun that lasted year long.

"This is the last stop, ma belle." The bus made a screeching sound, moaning pity for the fact we now had to walk under this horrible weather. We dragged our bags down, and I followed my mom down the stairs to walk for around 10 minutes, though it felt like hours, especially when my boots kept getting pulled down by the snow pile, or when I had to stop time and time again to fix my gloves, hats, scarf. Pulling all our belongings in uncomfortable too-tight mittens, leaving trails of the old past in the snowstorm and seeing it all get covered up with snow made me want to cry. A sudden feeling of loneliness enveloped me, but I was sure that my tears would freeze on my cheeks, so I held them in.

The walk to my apartment was disturbing. I had never gone anywhere unfamiliar. I had never seen outside of Haiti; the snow I encountered was snow from pretty crystal balls gifted to me on a hot Christmas morning or shimmering in tv—not in the middle of a storm where my mom and I desperately walk down the side of a road.

We stopped in front of a tall, long building. There are many of those in Canada: long, thin structures that stand proud of their beauty. In Haiti, the houses are low, and the only things that reach the sky are the tall coconut trees. I assumed that this whole building was for my mom until she stopped in front of a tiny pale blue door, smiled at me, and laughed at a joke that I did not hear.

I looked down to see her hands turning the rusted doorknob which open to a narrow hallway that smelled of Clorox mixed with a hint of fried plantain. It lingered in the apartment and seemed to welcome my presence saying 'We have been preparing for you. Hope it doesn't bother you. We have even cooked.' The house in Canada did not smell like Haiti's beaches, nor had the open windows or doors of freedom.

The place had many envelopes with ‘past due’ in red and calling cards in every corner. The television had a melancholy song about 'God I need you.' The place seemed like home with a large brown couch, a dining table with fruits like papayas, mango, and avocados, and a big picture of the Haitian flag with a white Jesus on the cross right beside it. Yet I did not feel at home; I felt tired. I was in a place where we had to wear immense coats, uncomfortable mittens, and walk in slippery brown snow, not back in Haiti, where we spent days lying under the sun drinking coconut juice and playing by the beach.

As I took off my boots, I realized how dirty they were with snow that had somehow entered my boots, how much I hated winter, how much I hated the snow and how much I hated the red bus stop. I smiled at my mom. She mentioned leftovers and that I should get washed up. Haiti was an airplane, a bus stop, and a snowstorm away from me, so I made myself at home.

Danie Maxelus, a 21-year-old Haitian-Canadian residing in Ottawa, Canada, is a passionate aspiring author and advocate. Currently pursuing a degree in English with a concentration in creative writing at Carleton University, Danie immerses into the world of literature and music. Eager to utilize creative expression for advocacy, Danie seeks opportunities to amplify marginalized voices and bringing attention to their unique narratives.